by Ron Ploof | Jun 20, 2016 | Business Storytelling

Most business presentations fail because they’re stuffed with too much information. Rather than selecting the most relevant facts, presenters force their audiences to sift through a mound of data to find the golden nuggets contained within.

Business storytellers do something different. Rather than forcing a listener to pan for the gold, storytellers place whole nuggets into their pans, leaving them to ponder how the chunks got there. In other words, storytellers don’t just state facts, they make story statements.

Let’s take a look at the difference using the following famous sentence:

The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog.

The sentence contains a simple fact. It’s like saying the sky is blue, the product is rated number one, or the company hit its quarterly goal. There’s nothing that a listener can do with this information other than to just accept it passively. However, by making a slight modification, we can transform this factoid into a story statement.

The quick brown fox wanted to jump over the lazy dog.

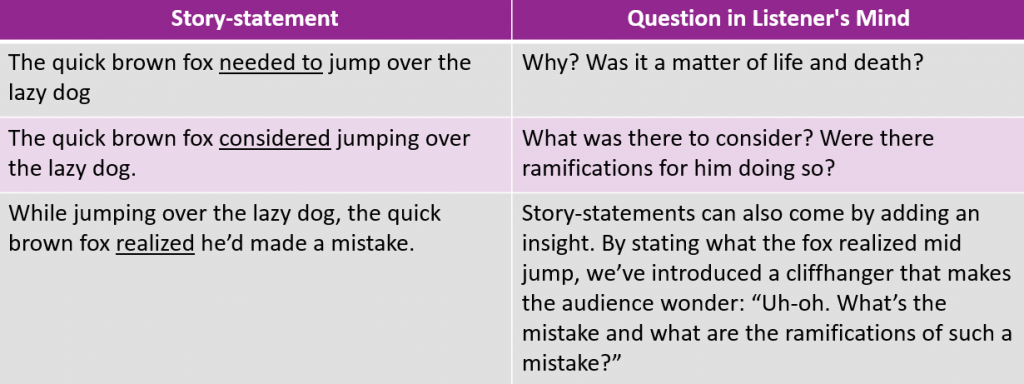

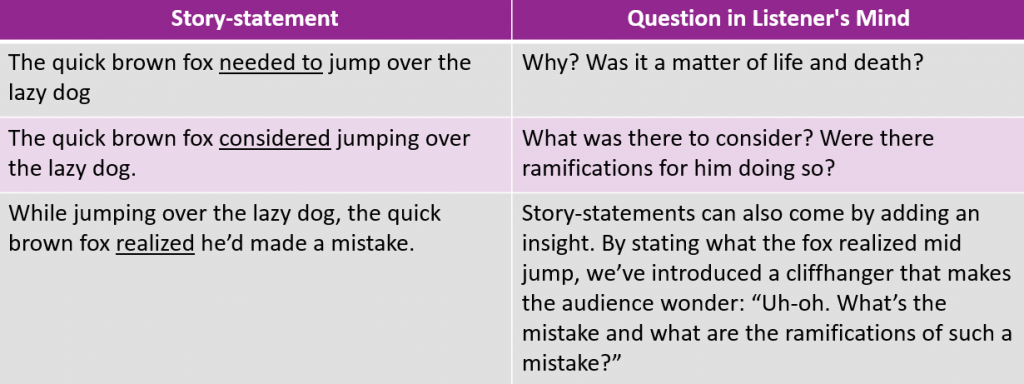

Story statements do two things: deliver a fact while simultaneously spawning a question within a listener’s mind. When listeners hear a story statement, their Neural Story Nets compel them to wonder what comes next.

- Why did he want to jump over the dog?”

- “Did he make it?”

- “Is there something that’s keeping him from doing so?”

By stating what the fox wants instead of what the fox did, storytellers transform an audience from passive listeners into active participants.

Here are some story statement alternatives:

In each of these cases, we’ve modified the facts in such a way that compels the audience to want to know more.

Think about your next business presentation. List the most important facts that you must convey. Now, rather than spewing them rapid-fire, turn them into story statements. If you deliver them correctly, your audience will feel as an integral part of your presentation rather than a passive target to dump data upon.

Photo Credit: Library of Congress

by Ron Ploof | Dec 18, 2017 | Business Storytelling

Our goal at the StoryHow Institute is to be your go-to business storytelling resource by publishing strategies and tactics that you can use to become a better storyteller. We fulfilled that promise in 2017 through publishing the following 38 storytelling articles. We look forward to serving your storytelling needs in 2018.

1. Storytellers Put Chips on their Character’s Shoulders

The best storytelling lessons come from life. This one comes from NFL star Martellus Bennet.

2. Storytellers Stir Beer with Steak Knives

The most important skill that a storyteller can have is a keen sense of observation.

3. Storytellers Break Patterns

Our prior experiences hold an unfair advantage over our newer ones because they can cause us to react in seemingly incongruous ways.

4. The Best Stories Start with an Oops

Most companies dread mistakes. But the best stories tend to follow them.

5. Storytellers Find Stories Behind the Stories

Beginner storytellers are so focused on the primary story that they miss opportunities to add deeper meaning and memorability to them.

6. Storytellers Study the Masters: Paul Harvey

Master storyteller, Paul Harvey, not only dazzled audiences for over fifty years with his show The Rest of the Story, but he also proved the business value of a story.

7. Storytellers Use Elbow Grease, Time, Thought & Persistence

Most people think that the creative process requires waiting patiently for inspiration to strike. Glenn Frey, co-founder of the Eagles, learned that it required something else…work.

8. Storytellers Don’t Own Too Many Things

Beginner storytellers cram their stories with too many ideas, facts, threads, and characters. As a result, they’re forced to take care of those things, which draws time from the most important tasks, like serving their audiences.

9. Storytellers Study Foods that Begin with the Letter Q

Stories and the human memory are interdependent. Memories can’t work without stories and stories can’t work without memories.

10. Storytellers Love Circumstantial Evidence

Characters are the seeds of any story. Storytellers plant them in the fertile ground of circumstance and water the two with their individual wants.

11. The Only Way to Become a Storyteller is to Tell Stories

You can’t play the game by sitting on the sidelines. If you want to become a better storyteller, you’ve got to act the part.

12. Storytellers are Policy Wonks

What do robots and storytelling have in common? Policies, or the way each is encouraged to react in certain situations. Storytellers, like artificial intelligence researchers, put characters into situations, assign them policies, and see how they react.

13. Storytellers Don’t Confuse the Story with the Telling

It’s common for first-time storytellers to focus more on the story than the actual telling.

14. Storytellers Love Improbable Moments

Storytellers love improbable moments because odds-defying experiences break us out of our routines, make us pay attention, and therefore, frequently contain the seeds to some story.

15. Storytellers Study Allergic Reactions

Sometimes the words that we use can initiate strong reactions within people. That’s why storytellers study allergic reactions.

16. Storytellers Shine During Story Moments

Stories hinge on story moments–specific times when a character’s choice will alter the story’s trajectory–but not in the way that the audience expects.

17. Storytellers Take the Window Seat

Storytellers live in the moment, observing life and reflecting upon what they experience. They do so by putting themselves in the window seat.

18. Part 1: The Science Behind How Stories Connect Us

This science experiment demonstrates how our brains synch-up when we tell each other stories.

19. Part 2: The Science Behind Stories and Memory

The second of a two-part series that looks at the brain science behind storytelling. In Part #1, we saw how the brains of listeners and storytellers synchronize during the course of a story. This time, we watch people’s brains while they recall one.

20. You Can’t Get Hurt Watching Television

We all tell ourselves stories. In this blog post, Ron describes how one particular story convinced a man to remain focused on his job while bullets whistled by his head.

21. Storytellers Eat with Sailors

All stories are mysteries. Some are just bigger than others.

22. Storytellers Say More with Less

Most story novices think that story development starts by focusing on the big things like the plot, the struggle, and the final resolution. But, that’s not where the magic of storytelling resides. The best storytelling lives in the little details that hit audiences in the gut and make us feel a kinship with the characters.

23. Storytellers: Beware of Singing Bridges

Storytellers set believable hooks that satisfy audiences as opposed to stringing them along. Those that don’t will suffer the consequences.

24. A Five Star Rating Doth Not a Business Story Maketh

While 5-star reviews may make us happy, they aren’t very valuable from a business storytelling perspective. In this article, Ron examines the business value of the one, two, three, four, and five-star product review.

25. All Storytellers Fall the First Time

It doesn’t matter how much skill you have as a storyteller. Nobody can tell a brand new story without thinking about it first. And the science backs it up.

26. Storytellers Tackle Ethics with DOTS

Storytellers have an ethical responsibility to help their audiences. Simultaneously, storytellers must counterbalance that obligation by making stories interesting. So, where do they draw the lines? How do they choose which facts to use, omit, and modify while maintaining the integrity of the story? We suggest using DOTS.

27. The Best Stories Start with Partial Information

Great storytellers reveal just enough information to let an audience’s imagination run wild, before dropping one last piece of context that turns every assumption upside down.

28. The Creative Catalyst

Kip Meacham, Vice President of Marketing for CA Engineering, used his copy of the StoryHow™ PitchDeck so much, he wore out the box.

29. Storytellers Use Blind Spots

We all have blind spots–things that obstruct our ability to perceive the full scope of a situation. And they are very useful for storytellers.

30. The Best Story Tellers are Avid Story Students

The best way to learn storytelling is to immerse yourself in the work of others for a second, third or fourth time.

31. Storytellers Use Tools of Mass Induction

The best storytellers use techniques that keep their actively audiences involved in the story.

32. Storytellers Dole Out Information

Storytellers choose which information is released and who is privy to it.

33. Storytellers Use Anchors

Storytellers use anchors to set memories in the minds of their listeners.

34. Storytellers Use Recurring Events to Bond with their Audiences

Storytellers use recurring events (StoryHow PitchDeck Card #18) to anchor stories. They can be used to establish a historical foundation that can shape a story’s future. The best part is that audiences easily relate with them.

35. Storytellers Find Stories in Last Days

Last days signal change and all stories are based on change.

36. Storytellers Use Red Flags

Red flags are a special case of story statements. Use them well to pull audiences into your story.

37. Storytellers Chisel Stories out of Hidden Agendas1

Storytellers love hidden agendas because they form the chalk lines on story stones. Simply chisel along those lines and an interesting story emerges.

38. Storytellers Love Awkward Moments

We’ve all been there before–either experiencing a cringe-worthy moment or witnessing one. Storytellers love awkward moments because they’re not only filled with both internal and external conflict, but they are relatable to the audience.

by Ron Ploof | Nov 20, 2017 | Business Storytelling

Let’s try writing the beginning of a story.

It had been a long day. Sandy couldn’t wait to get home, change into comfortable clothes, and relax in front of the television. She pulled into her driveway and noticed the darkened front steps. ”That’s odd,” she thought. “Did that porch light burn out again?”

She fumbled with the lock in the darkness, but the door swung open before she could insert the key. She wondered whether she’d closed the door earlier that morning. Rather that thinking too much about it, Sandy entered the house and locked the door behind her.

Got it? So, what’s going on here? Is everything okay with Sandy? Do you have any concerns for her safety? If so, why? The bare facts don’t explicitly tell us that she’s in any danger. She might be walking into a safe empty home, a dangerous ambush, or a surprise party organized by her best friend.

Red flags are special story statements. They’re odd little facts that just don’t seem right. Did you wonder why the porch light was out or the front door was ajar? Storytellers evoke those questions using red flags. Red flags force listeners to anticipate uncertain future events and the listener’s mind will not rest until they’re answered.

Red flags draw audiences into the story. They help listeners care about the characters and have been known to make people in darkened movie theaters scream out, “Don’t go in there!” or “Don’t do it!”

Yet, it’s curious that few marketers ever use them–especially in success stories. Success stories are vehicles that marketers can use to help prospects get a feel for products and services. For example, here are some potential opening lines:

- Jered had estimated that his cell phone battery had at least an hour left on it.

- Monica wondered why the assets on the balance sheet were significantly lower than last week’s.

- Scott’s hard drive had been making an annoying clicking sound for the past two days.

Each line contains a red flag, something that the audience can relate with and the storyteller can build upon.

Are you wondering how to start a success story? Consider using a red flag.

Photo Credit: Rothstein, Arthur, photographer. Sneaking under the circus tent. Roswell, New Mexico. Chaves County New Mexico Rosewell, 1936. Apr. Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/fsa1998018640/PP/

by Ron Ploof | Oct 9, 2017 | Business Storytelling

Before one tells a story, three things must happen. You must find someone willing to listen, they must have some interest in the subject, and they must have the time necessary to hear it. Then, it’s the storyteller’s job to hold their attention for the duration.

We’ve already discussed one attention-retaining technique: story statements–dual-purposed sentences that deliver factual information while simultaneously opening questions within a listener’s head. Story statements rely on the human brain’s propensity to question things. So, as long as your story continues answering those questions, you’ll continue to earn audience attention.

Today, we turn to another storytelling induction tool: the open-ended question. While story statements induce listener questions, open-ended questions induce listener ideas.

Storytellers are open-ended question masters because they focus on getting to the center of the story. They know that the best way to do so is to ask questions that can’t be answered with a simple yes or no. Why? Because open-ended questions draw deeper answers.

For example, let’s say that you’re trying to draw a success story out of a client. The following closed-ended questions won’t help much:

- Were you happy with the service? (Yes/No)

- Did you increase sales? (Yes/No)

While closed-ended questions will always evoke a response, the answers aren’t story worthy. However, if you tweak the questions just a little bit, you’ll get much deeper answers:

- What was your favorite part of the service?

- How has your sales responded since the service?

These questions demand more from respondents, forcing them to be more thoughtful with their answers.

And then there’s my ALL TIME FAVORITE open-ended question. “How so?”

“How so?” is the ultimate tool of mass induction. When used as a follow-up question to a previous answer, it forces the respondent to provide even more depth by adding nuances like context, prioritization, and comparisons.

Give tools of mass induction a shot. Try using story statements, open-ended questions, and your new secret weapon, “How so?” They just may help you find the center of your next story.

Photo Credit:

Herford, Oliver, Artist. Frenzylogical Chart. , 1917. Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2010716595/.