“Where do you draw the line between storytelling and the truth?” a student asked me after my lecture at the USC Marshall School of Business last Monday. Although I sensed where the question was going, I asked for a clarification.

She glanced sheepishly at her fellow MBA candidates. “Well, I know it’s part of doing business, but how far should companies take storytelling?”

“Stretching the truth is not a good business strategy,” I said. “And using the power of story to do so is even worse.”

I offered her a quote from Daniel Wallace, the author of the novel, Big Fish.

“A storyteller makes up things to help other people; a liar makes up things to help himself.”

I love this quote because it focusses on the intent of the storyteller instead of the story itself. If a storyteller is motivated by informing, enlightening, or bringing meaning, she’s put the needs of the audience before her own. Yet, if another storyteller wants to embellish, deceive, or spin, he’s put his needs first.

Storytelling, as with any human invention, is morally agnostic. Dynamite, invented by the Nobel Prize’s namesake, can be used for either construction or destruction–which can only be determined by the will of the user. We don’t have to look far beyond today’s headlines to see the power of story being used for both good and evil.

One of my favorite pieces of content marketing comes from the 1920s when financial institutions wanted to encourage their customers to save money. They turned to George S. Clayson, a financial writer who taught personal finance lessons through little parables. Banks and insurance companies initially distributed these stories as pamphlets, but demand for them rose so high that Clayson published his collection of parables as a book. If longevity is an indication of a book’s success, consider that The Richest Man In Babylon is still in print eighty-six years later.

Most companies dismiss fictional story forms because they assume that fiction means fake, and fake means deception. But just because a story is written as fiction, it doesn’t mean that its message is untrue. Aesop taught life lessons through stories featuring talking animals. We know that tortoises and hares don’t have street races, but that doesn’t negate the fundamental truth that slow and steady wins the race.

It all comes down to the intent of the storyteller.

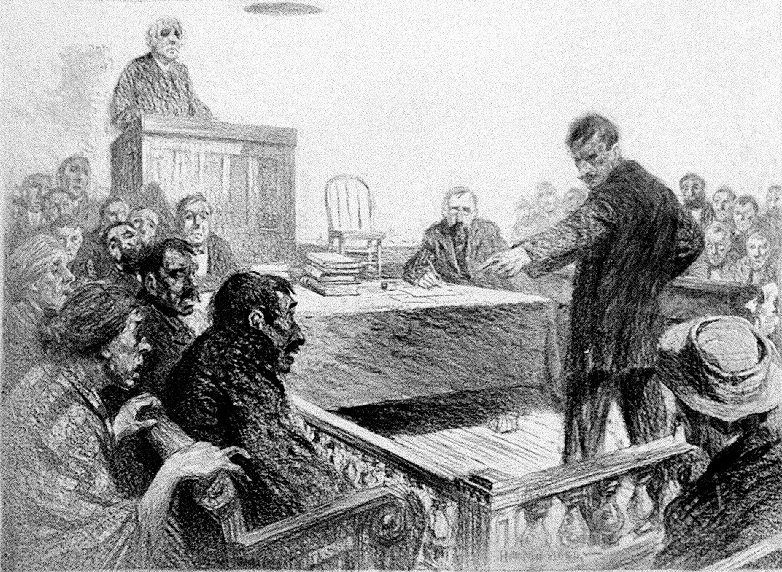

Photo Source: Library of Congress